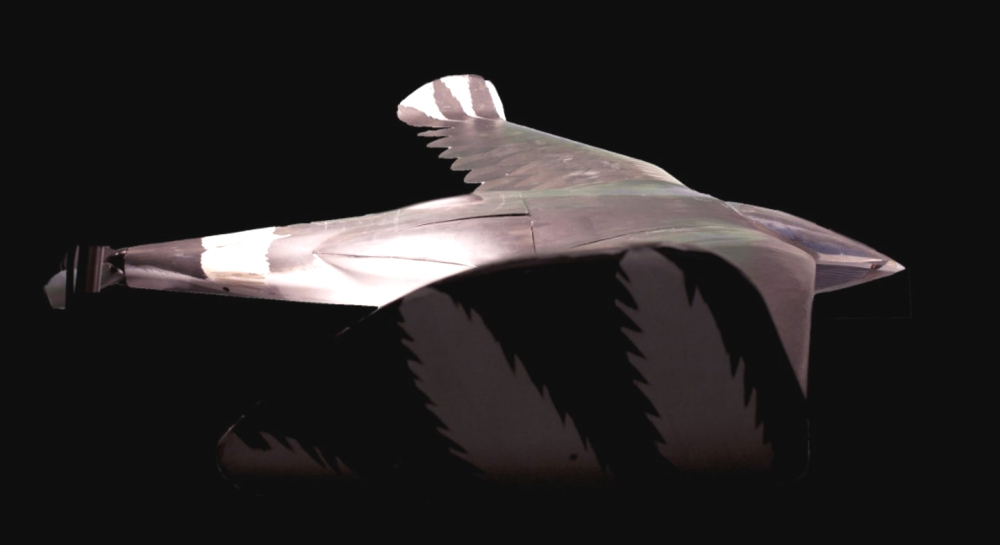

In the late 1960s the CIA began developing a small bird-like drone, intended for low-profile aerial reconnaissance. Still stinging from the infamous loss of the U-2 aircraft and pilot Francis Gary Powers in Soviet airspace in May 1960, the CIA looked to the concept of unmanned aerial vehicles which represented a lower-risk alternative to manned flights over the Soviet Union and China.

Project AQUILINE was one such concept. Developed in partnership with the McDonnell Douglas Corporation and tested at Area 51 in Nevada, this drone had the appearance of a large bird if viewed from a distance. It was 5.5 feet long with a 7.5-foot wingspan and had a tail-mounted pusher propeller. It could fly for up to 50 hours before recovery. At least five prototypes were built during the project’s development phase.

AQUILINE took the opposite approach to previous reconnaissance overflight operations. The U-2 spy plane was intended to fly so high that it could not be intercepted by Soviet aircraft or ground-to-air missiles of the day. It could be detected but not intercepted. The AQUILINE drone would fly so low and slow that it would be seen with the naked eye, but subsequently dismissed as just another bird sailing on the air currents.

It was launched via an inclined rail system, and recovered by a net strung between two poles, where it would be gently guided by the remote operator. There was also an effort to make it recoverable in-flight by helicopter, a strategy which had already been successfully implemented with the BQM-34 Firebee drones used during the Vietnam era. This was likely to allow for recovery over the ocean instead of waiting for the drone to fly back to a safe landmass.

The drone was also intended to be able to hover over its intended target for up to 120 days, presumably without extensive directional travel to conserve fuel. There was a television camera mounted in the nose to aid with navigation and also to produce video footage of its reconnaissance targets.

Although unarmed, AQUILINE was developed with a sensor emplacement capability. The goal was to drop black box sensors near enemy missile testing ranges, nuclear facilities, biological/chemical warfare research facilities, and other prime targets. These solid-state sensors were the product of microminiature technology development and needed to be dropped from a relatively low altitude when compared to previous overflights by the A-12 OXCART or U-2 spy planes.

There was even an intended capability to support agents in place. This likely meant that rather than dropping black box sensors, AQUILINE would be able to ferry in a payload of espionage tools or even weapons to a local agent or CIA employee who had successfully entered a hostile country by traveling without any incriminating tools or equipment.

To enable long range operations the CIA researched many types of power systems including fuel cell generators and even a radioisotope engine. This meant that Project AQUILINE might carry the U-238 radioactive isotope, which would generate enough heat to power its flight apparatus, a concept which had previously only been used for deep space satellites. Essentially a simplified micronuclear generator, in the early 1970s.

Ultimately this project was scrapped and never widely implemented. McDonnell Douglass was unable to continue development within the CIA’s intended budget threshold of $11,000,000. Development ended and the CIA pursued other more plausible means of conducting safe reconnaissance over its Cold War targets.

The US government pursued many fascinating and secretive technological projects during the Cold War, often with mixed results, as covered in the outstanding book Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed by Ben Rich.