Unbreakable: 949 Days in a Cuban Prison

The Mission

In 1960, three technicians from the CIA’s Technical Services Division were dispatched to Havana, Cuba, to install surveillance equipment in a building soon to be occupied by the Chinese embassy. The three men: David Christ, Thornton Anderson, and Walter Szuminski were not case officers or field operatives; they felt more at home in a laboratory than in a hostile environment. In fact, this mission was Anderson’s first assignment outside of the United States. Their work in Cuba was part of a move by the CIA to integrate technical collection activities more closely with field work. Previously, case officers had used standard spycraft such as dead drops and personal meetings to accomplish their missions. The rapid progress in miniaturization of technology during that era was largely unknown to case officers.

This operation was driven by two key factors; Chinese intentions in the Caribbean were one of the CIA Far East Division’s highest priorities, and the rapidly decaying opportunity for permissive operations in Cuba. Fidel Castro had just seized power in Cuba the year prior, and no one in the US quite knew what to make of him yet. It was hoped that Castro could be swayed to become an American ally. But he was already making overtures to the Soviet Union, and now China. Learning what was to come of this impending alliance was a critical requirement for the CIA. The combination of a high-value target and a diminishing window of opportunity led the CIA to act in haste; and in the world of spycraft, haste can lead to disaster.

The three technicians arrived in Cuba with only the shallowest of cover identities. They possessed US passports and drivers’ licenses with falsified names but did not have an extensive backstory set up for verification should they be detained or imprisoned. For example, the home address for Szuminski’s alias was the home of his current girlfriend, who was unaware of his status with the Agency. If someone knocked on the door asking for “Edmund Taransky”, she would truthfully answer that she knew no one by that name.

This was to prove to be a mistake soon after their arrival.

The Arrest

Upon arriving in country, the first snafu presented itself immediately. The owner of the building soon to be occupied by the Chinese embassy was no longer cooperating with the Americans. However, another target had presented itself in the meantime. The New China News Agency would be renting space in Havana, and a CIA asset conveniently already lived in the apartment directly above theirs and was willing to allow the surveillance team to emplace listening devices in his apartment, directed at the news agency one floor below.

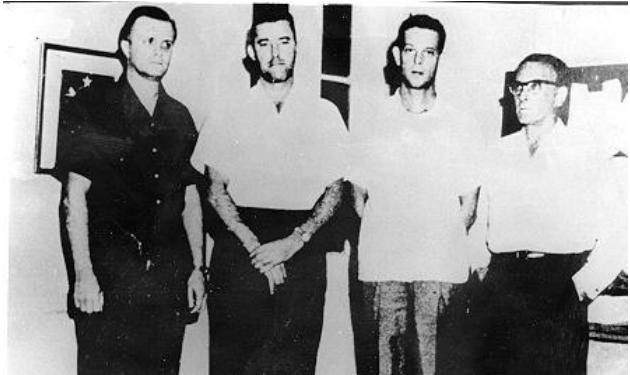

While working diligently in the CIA contact’s apartment, drilling holes and installing wires and a power source for the hidden microphone, Cuban authorities burst into the room with weapons drawn. It is unclear how the men were discovered; possibly due to a surveillance operation against them. The men were roughly searched, and then herded into the back bedroom of the apartment they had been bugging. The men claimed that they were all tourists just as their cover identities described. They explained that while visiting Cuba they had been asked by an embassy employee to do a little electrical contracting for him; an incredibly flimsy story, but one that they stuck with for the entirety of their coming three-year ordeal.

The CIA men were held in the bedroom overnight in complete silence as the Cubans waited in ambush, should anyone else arrive as part of the team. The long night was nerve-wracking for the technicians, but their Cuban captors became bored and eventually started playing with their issued revolvers. One policeman accidentally shot himself in the hand inside the apartment as the night dragged on. This general lack of professionalism among the Cuban authorities would be to the advantage of Christ, Anderson, and Szuminski as their confinement dragged on.

In hindsight, it was clear that some corners had been cut in an effort to conduct this operation as quickly as possible, before US-Cuba relations completed deteriorated. David Christ had visited the island a few weeks earlier under cover as a tourist and had reported to a fellow CIA employee that he believed he was under surveillance at that time. Someone else should have gone in Christ’s place on this mission, but a confluence of factors meant that no one else was available at the moment. Several audio engineers were on vacation or transitioning to other permanent duty stations. And Hurricane Donna was bearing down on the region, meaning they couldn’t afford to wait since it was unknown how travel would be affected once the hurricane arrived.

Christ’s presence on the mission was in and of itself a huge risk at the time. The CIA considered him to be “probably the most knowledgeable officer in the Agency of world-wide audio operations.” If he were to break under harsh interrogation, technical collections operations all over the world might be compromised. Thousands of man-hours of work, millions of dollars spent, and personnel put in immense danger while operating overseas. Christ could prove to be the weak link that broke the entire chain.

In the aftermath of his arrest, the CIA risk assessment noted that Christ had knowledge of:

- All audio operations world-wide since December 1957 to present date.

- Complete knowledge of all R & D aspects of audio equipment research.

- Complete knowledge of all audio assets in production and stocked for use overseas.

- Clearances through Top Secret, Special Intelligence clearance, and”Q” clearance.

- World-wide knowledge of the location of all audio technicians.

- Having previously been with the Applied Physics Branch of TSD, he was also aware of many other R & D activities.

- As the Audio Branch Chief in TSD, he has full information on all personnel in TSD and general knowledge of the overall activities, including the research programs.

Even worse than his knowledge of worldwide operations was a fact the CIA could hardly bear to think about; not long before his disastrous trip to Cuba, Christ had been briefed on the planned invasion of Cuba. The date and location had not yet been settled at that time, but if he broke under interrogation, Castro’s forces would be fully prepared for one of the CIA’s largest-ever covert operations.

Fortunately, Christ proved himself to be an astonishingly resilient leader throughout the entire ordeal, and never provided actionable intelligence to anyone, despite everything he was put through.

Interrogations at the G-2

For the next 29 days, Christ, Anderson, and Szuminski were held prisoner at the G-2 headquarters. This nascent organization was at the time, highly disorganized and unprofessional. The G-2 would not in fact be officially organized until the following year, 1961. At the time however, they were already an organization to be feared. Over the coming years the G-2 would work closely with the Soviet KGB and grow to be an incredibly capable entity in its own right. The G-2 would later run a series of highly damaging agents within the United States, including Ana Montes, a career analyst at the Defense Intelligence Agency, and Walter & Gwen Myers, who spied for Cuba from 1978 until their arrest in 2009. Walter was a State Department analyst with a Top-Secret clearance.

However, in 1960 the organization had a long way to go before it would become the formidable adversary it became in later years. Each of the three men were interrogated at least four separate times that first month. Their primary interrogator was someone they began to call “Bad Teeth” since they never learned his name. Bad Teeth was not an experienced interrogator and would slowly page through a training manual to determine what approach to take next. He skipped all around in the book based on his whims. Anderson said that if the man had actually paid attention and gone through from beginning to end, the Americans might just have been broken eventually.

As their days in the G-2’s prison cells dragged on, Christ made peace with the idea that he might just be executed by the Cubans for his suspected crimes. As team leader, Christ did everything he could to shift the blame away from Anderson and Szuminski, and onto himself and the unnamed (fictional) embassy employee who had requested their electrical work. He later stated, “…I kept thinking of my two sons. I just made up my mind that if I had to get shot, that’s where I was going to be, and I wasn’t going to do anything to disgrace my country. I didn’t ever want any stigma to be passed on to my sons.”

Trial at La Cabaña

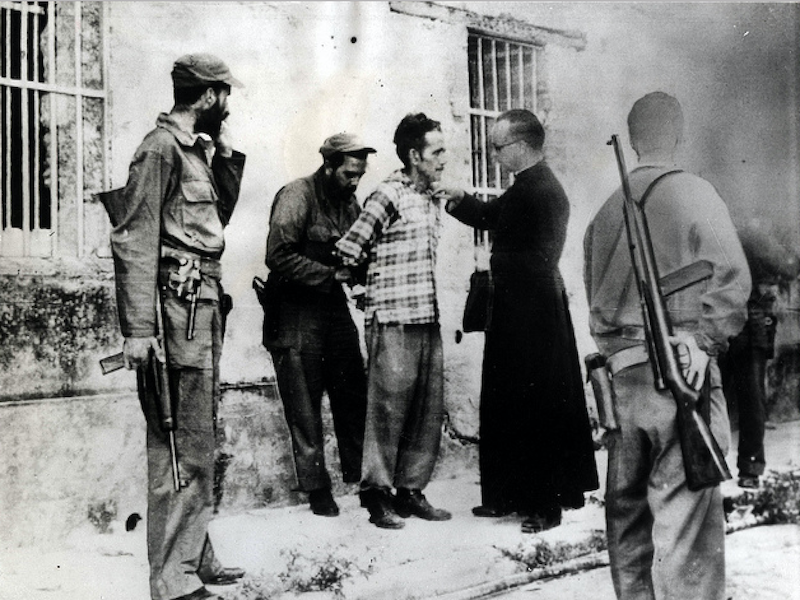

After nearly a month in the cells of the G-2 in Havana, the men were transferred to La Cabaña, where they would spend the next 101 days awaiting trial. The facility was disgusting and barren of anything approaching comfort or even livability. As a transient center, prisoners were constantly brought in and taken out again, many to be executed there on the grounds. Christ, Anderson, and Szuminski were often awakened to the sound of gunfire as a fellow prisoner was executed just a few yards away.

Hundreds of prisoners were executed at La Cabaña in the early days of Castro’s rule. On the day of their show trial in December 1960, the three CIA men were led past the execution grounds on the way to the courtroom. Anderson recalled seeing bits of human remains from the most recent executions still plastered to the bullet-riddled wall.

The trial of the accused lasted for approximately four hours. After their long detention, there were a few brief moments of hope that shown through that day. The American Consul, Hugh Kessler made an appearance as their representative. And the prosecution did not demand a death sentence as the men had expected, but rather 30-year prison terms. While awaiting sentencing after the trial, Kessler was positively glowing, telling the men that they’d done great jobs on the stand. He even bought them Coca-Colas from a vending machine and left that afternoon promising to see them on the next visitation day.

That was the last time the men would see a US Government representative for more than two years. A few days later the United States withdrew diplomatic recognition of the Cuban government and closed the embassy in Havana. The three Americans were sentenced to 10-year prison terms for “activities against the security of the Cuban state” and transferred to their third and final location to serve out their sentences.

Life in Presidium Modelo

In January 1961 Christ, Anderson, and Szuminski were transferred to the Presidium Modelo on the Isle of Pines (now known as the Isle of Youth), south of the main island of Cuba. This horrible, overcrowded prison would be their home for more than two years. Castro himself had been imprisoned here after his 1953 attack on the Moncada police barracks. And despite his treatment there (or perhaps, because of it), used the facility to incarcerate all who he believed opposed his burgeoning dictatorship. His regime had already relegated approximately 6,000 political prisoners there. Most were upper class Cubans, such as journalists who had published an unflattering portrayal of the events of the revolution.

The Presidium Modelo itself was a monument to cruelty and desperation. Constructed in the 1920s to house approximately 4,500 prisoners, it was now overcrowded and filthy. It’s five circular buildings held hundreds of cells each, with no cell doors to keep the prisoners confined within. The main floor was a common area with an enormous watchtower with dark tinted windows built in the exact center. Guards entered and exited through a subterranean tunnel so the prisoners never saw them, and never knew who they were observing at any given moment.

On their first day at the jail, the men were able to get two adjoining cells inside Circular Four, so they stayed together for the duration of their sentences. Beds were in short supply but the men were eventually able to purchase beds from other prisoners at a price of 30 pesos. Hungry prisoners were willing to give up their only creature comfort in order to buy a little extra food for the day.

For the first month, their attorney paid a local family to deliver them extra food, and they ate much better than the other Cuban prisoners. But even this single benefit diminished over time as the delivered food was of worse and worse quality. All three men lost between 30-70lbs each during their stay at the Presidium Modelo.

Incredible stress and pressure were their constant companions. The men stood out as Americans among thousands of Cubans. They were under threat by various groups within the Presidium throughout their incarceration. The prison was lawless place, and riots were commonplace. Suicides occurred with alarming frequency as a prisoner could easily jump to their death over the railing at any time. The guards were known to open fire into the common areas at times, so ricocheting bullets were a constant threat even if you were minding your own business.

Earning Trust and Saving Lives

Somehow, despite the odds, the men made the best of their terrible situation. Despite feeling abandoned by their government, despite the constant cruelty of their incarceration and threat of death and disease, they persisted. They never gave up hope, nor honor. To their fellow prisoners they became trusted friends, and eventually leaders. In the worst possible situation, they used their unique skillset to turn the odds in their favor.

Christ, Anderson, and Szuminski circulated through the prison daily, offering encouragement and building rapport with their fellow inmates. They used their bilingual skills to interpret news from the region, and always advocated from a pro-Kennedy, pro-US standpoint. Over time, the men’s Spanish-language skills improved, and they even began to teach classes in English, and gave lectures on the US Constitution, capitalism, free elections, and other facets of American life. They acted essentially as agents of influence against the Castro regime from within the walls of its harshest prison. Presumably their fellow captors did not need much encouragement to see the consequences of communist rule.

hey also put their engineering talents to great use. With virtually nothing to work with beyond their own can-do attitudes, and ingenuity, the men set to work solving problems. They were able to create a slide rule out of an old cigar box, after finding an engineering textbook that had somehow survived for years in the prison.

After a great deal of scrounging and experimentation, they built a homemade radio. They used intravenous lines from the infirmary for tubes, a smuggled earpiece, and Russian transistors. The fabricated a battery using zinc from a pail, copper from stripped electrical wires, and copper sulfate from medical supplies. The tuning coil was copper wire wrapped around an empty cardboard toilet paper tube. The radio worked well enough to pick up broadcasts from Key West and New Orleans. The men were able to climb out on the roof one night and listen to American music for the first time in nearly two years.

With the radio finally linking them to the outside world, they went one step further and created an underground newspaper for the prisoners. Enlisting a former radio operator and a former legal secretary to act as a stenographer, they began printing a daily hand-written newspaper to circulate among the prisoners.

They also prevented at least one suicide by grabbing a man who was preparing to jump off of the fifth level balcony and talking him down from his fit of hopelessness. The man, a Cuban astrologer who had sealed his own fate by predicting Castro’s downfall in his newspaper column, survived the day and did not make another attempt.

Richard Pecoraro was an American soldier of fortune who had lost his mind during the long prison sentence. He was filthy and no longer spoke, only snarling at anyone who came along to bother him in his agitated state. The three other Americans worked to befriend him and arranged for a Cuban psychiatrist among the prison population to spend time with Pecoraro and provide therapy via a translator. They even arranged for a supply of Valium to be sent to Pecoraro from outside the prison walls.

Placing technical geniuses like Christ, Anderson, and Szuminski in the Presidium Modelo may have been one of the regime’s greatest mistakes. Nothing the system did could break their spirits, and they constantly found ways to beat their communist oppressors at their own game. The men became trusted friends and leaders among the thousands of Cuban political prisoners.

The Invasion

In April 1961 the CIA-led invasion at the Bay of Pigs began with a boom. The prisoners were awakened by the sound of anti-aircraft fire from the roof of the prison. Looking out the windows they watched as an American B-26 bomber flew straight over the prison, bombing a Cuban patrol boat in the waters just off the coast. Christ, Anderson, and Szuminski had long suspected an invasion might take place but hadn’t known when it might happen. Now, the attack was on.

Over the next few days everyone waited with dwindling hope for more news of the invasion. It was logical that the Presidium Modelo might be a strategic objective for the rebels. With thousands of prisoners from the Cuban educated class, as well as captured American mercenaries and the three CIA men themselves, it stands to reason that the CIA and the rebels would want to liberate the prison as quickly as possible.

But the sounds of an attack never moved closer. No liberators arrived. Days later they learned that the rebels had been defeated at the beachhead. No one was coming to rescue them. Dejected and near hopelessness, everyone waited for what was to come.

Defusing the Bomb

After the failed invasion, Castro took steps to ensure that no one from the Presidium Modelo would ever be rescued by an invasion force. He ordered the extraordinary measure of mining the entire prison with thousands of pounds of TNT explosives, so as to destroy the entire facility and kill all of the prisoners with the push of a plunger, if it became necessary.

For three weeks, military demolition specialists used jackhammers and air compressors to cut holes in the support pillars of each building and ran a buried conduit far away to a point outside the perimeter fence, well out of the blast zone. Military cargo trucks soon delivered crates of explosives to the prison, with an estimated three tons buried beneath each of the five circulars.

In this moment of greatest peril, the thousands of prisoners now turned to the three captive Americans to save them. A former Cuban Air Force officer named Captain Miro organized the prisoners and requested help from the three mysterious Americans. The CIA men rose to meet the challenge, as they had time and time before.

A plan was immediately enacted to sabotage the explosives, using anything that could be scrounged as tools. They also had to figure out how to disable the explosives without leaving any telltale indicators of tampering. Every single prisoner was aware of the danger they were all in, so there was no real way to hide their activities. Anything they did would be common knowledge throughout the prison within hours. The men had to trust that the prisoners understood that they were all in this together, and that no one would turn them in to the guard force.

On the lowest level of the prison, a drainpipe was discovered that would lead to the buried explosives. Two Cuban prisoners loyal to Captain Miro were tasked with widening the whole, from five inches to at least twelve inches wide. Once this was accomplished, one of the smallest Cubans, nicknamed “Americano” was enlisted to slither his way through the whole and put eyes on the explosives. Americano was directed to bring back samples of anything he could find, so the technicians could get an idea of what they were dealing with.

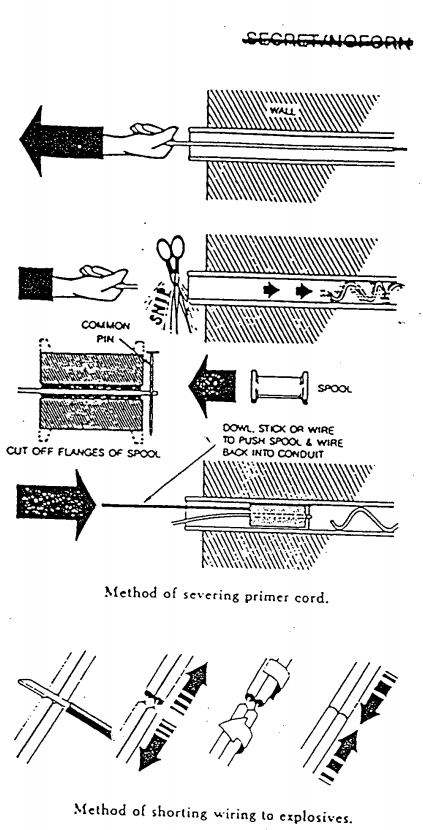

Americano soon returned with primer cord, blasting caps, a five-kg block of TNT, and a verbal description of everything else he’d observed. Now the technicians knew what they were facing, at least. The guard force had rigged the explosives with two separate initiators: the primer cord (a type of ultra-fast-burning fuse) and a standard electric wire detonator. They set to work on how to disable both initiators without the guards realizing that sabotage had occurred from within the prison walls. They had to come up with a way of cutting the fuse that would not lead to a limp line at the other end. If the guard force tested the primer cord line and found it to be slack, they would know immediately that it had been cut. And the electric wires had to continue carrying a current, on the chance that the guard force tested the wires with a galvanometer. What’s more, they had limited tools with which to handle the problem; just razors, knives, and sewing kits.

While David Christ worked to come up with a method of sabotage, Szuminski needed to come up with a plan for what to do in case they disabled the bombs, and the Cuban guards tried to trigger them and realized what had happened. He set to work with other prisoners to create improvised weapons in case they were needed for a prison break. Knowing they would only have minutes from the time the bombs were triggered until the guards realized who was really in charge of the prison complex, they would have to make a frontal assault on the main perimeter gate to have any chance of a mass escape.

With the TNT and blasting caps that Americano had salvaged from beneath the prison, Szuminski fashioned hand grenades using empty tin cans, rocks, and nails. Crude timer fuses were fashioned from IV tubing from the infirmary and ground-up match heads. Meanwhile, another Cuban prisoner who had been the chief chemist for the Bacardi rum company figured out how to distill alcohol from rotting fruit scraps and used this process to create Molotov cocktails. (He later created a perfect replica of Courvoisier cognac, using shoe polish for the color.) Szuminski was even able to come up with a homemade flamethrower using a spare kerosene stove. He created tight brass seals on the lamp’s fuel reservoir by polishing brass parts with a combination of marble dust and toothpaste. Pumping air into the reservoir built enough pressure to throw the fuel an acceptable distance. It could be lit by a handheld lighter as it sprayed out. Because of the open design of the circulars, the men worked in full view of the central guard tower, hiding their assembly efforts simply by turning their backs to the tower while working inside their cells. Once again, the carelessness of the Cuban authorities played to the advantage of the CIA men.

Once again, American ingenuity saved the day. The CIA men came up with a method using a sewing spindle to block the tunnel once the primer cord was cut, maintaining tension in the line. They also figured out how to short the electrical wire by cutting the insulation, twisting the wires into an X-shape to short them, then shoving the insulation back down over the twist, to hid it’s appearance from a cursory examination.

After devising this method, the men had to train Americano to perform the actual work. Knowing that he would be in a dark, confined space, surrounded by thousands of pounds of explosives, the men put him through a rigorous training program first. Americano practiced defusing the massive bomb upstairs in the cells while lying on his stomach, completely covered by a blanket to block out all available light. He went through the complex procedures again and again under realistic conditions in the pitch black until they ran out of pilfered materials to train with. The techs decided he was as ready as he would ever be. An hour before the final prisoner count of the night, they finally put the plan into action. Into the darkness Americano went… and out he came minutes later. Mission complete.

With the success in Circular 4, the detailed plan was passed through the informal prison network to the most capable men in the other Circulars. Days later word came back; the explosives in all five buildings had been successfully defused. Castro’s plan to obliterate thousands of prisoners at once had been defeated by the ever-resourceful American engineers.

Returning Home with Honor

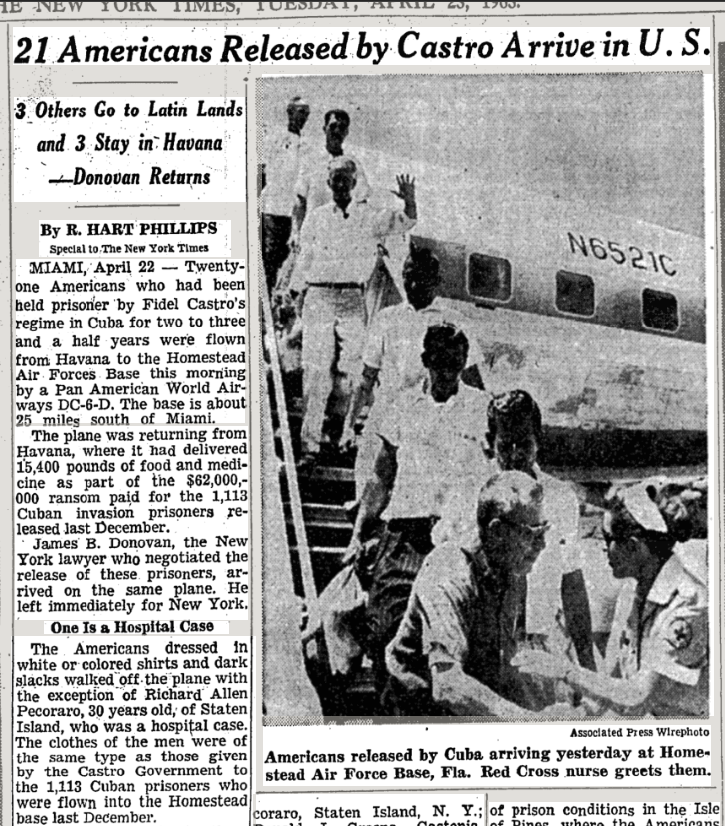

After more than nineteen long months in Circular 4, the men were transferred to the slightly more accommodating Circular 1. Negotiations were underway for their release. Famed attorney James Donovan had taken up their cause. A year earlier, he had successfully negotiated the release of CIA pilot Francis Gary Powers from a Soviet prison, and American student Frederick Pryor from the government of East Germany. Now, he had entered into face-to-face conversations with Castro himself for the release of many of the prisoners from the Bay of Pigs disaster. Donovan had traveled Cuba on a pro bono basis to negotiate the release of 1,113 prisoners. As negotiations continued, both sides made concessions. In the end Donovan and Castro came to an agreement to release the 1,113 prisoners from the Bay of Pigs, allow their families to depart Cuba with them (9,703 people in total), as well as the release of 37 additional American citizens including Christ, Anderson, and Szuminski. In exchange, Cuba received $2.9 million raised by private companies and charitable organizations; $53 million worth of medicine and baby food for the Cuban people; the release of four Cuban prisoners held in New York; and 17,500 tons of surplus food released by the US Department of Agriculture.

Nine hundred and forty-nine days after being arrested in that apartment in Havana, the men returned home to their nation and their families. On the flight with them were eighteen other Americans, including Richard Pecoraro, whom they had befriended and cared for inside the Presidium. Szuminski’s mother had passed away during their confinement; he only learned of it on the flight home. Anderson’s youngest son did not know him, and his older children barely remembered him. Szuminski eventually married his sweetheart Elsie, a CIA secretary who had waited all those years for his return. They had two children together.

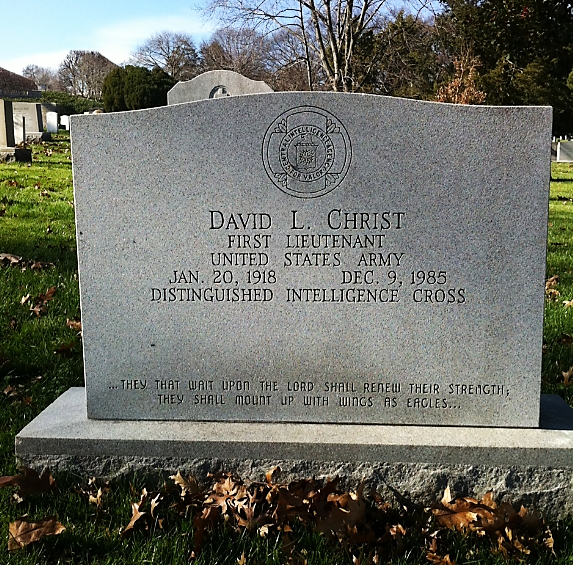

Christ’s days in the field were over; he took a high-ranking position in the Directorate of Science and Technology, contributing to the fight from there. He passed away in 1985 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Persecuted but unbroken, Anderson and Szuminski returned to the forefront of CIA operations. Five years later they were working together in a light aircraft belonging to Air America when they took ground fire during a collections mission.

All three men were eventually awarded the Distinguished Intelligence Cross (equivalent to the Congressional Medal of Honor) in 1979, after then-Director of Central Intelligence Stansfield Turner finally learned of their incredible exploits. In the 32-year history of the Central Intelligence Agency up until that point, only seven other men had been awarded the Distinguished Intelligence Cross.

The citation for each man’s award read as follows:

The DISTINGUISHED INTELLIGENCE CROSS is awarded in recognition of exceptional heroism from September 1960 to April 1963. During this period [the recipient] endured hardships and deprivations with unquestioned loyalty, great personal courage, and conspicuous fortitude. [His] exemplary conduct as a professional intelligence officer was highlighted by his unswerving devotion to the Agency and by his disregard for his own personal safety in order to assist others. [The recipient’s] performance in this instance reflects the highest credit on him and the Federal service.

Never once did their resolve waiver. Never once did they give the enemy what they wanted, actionable intelligence and a propaganda coup against the United States. Their Cuban jailers consistently underestimated them and never realized the full capability and resourcefulness of the men they imprisoned in the Presidium. They took everything a hardened communist government could throw at them and gave it back tenfold.

David Christ. Thornton Anderson. Walter Szuminski. Remember their names.