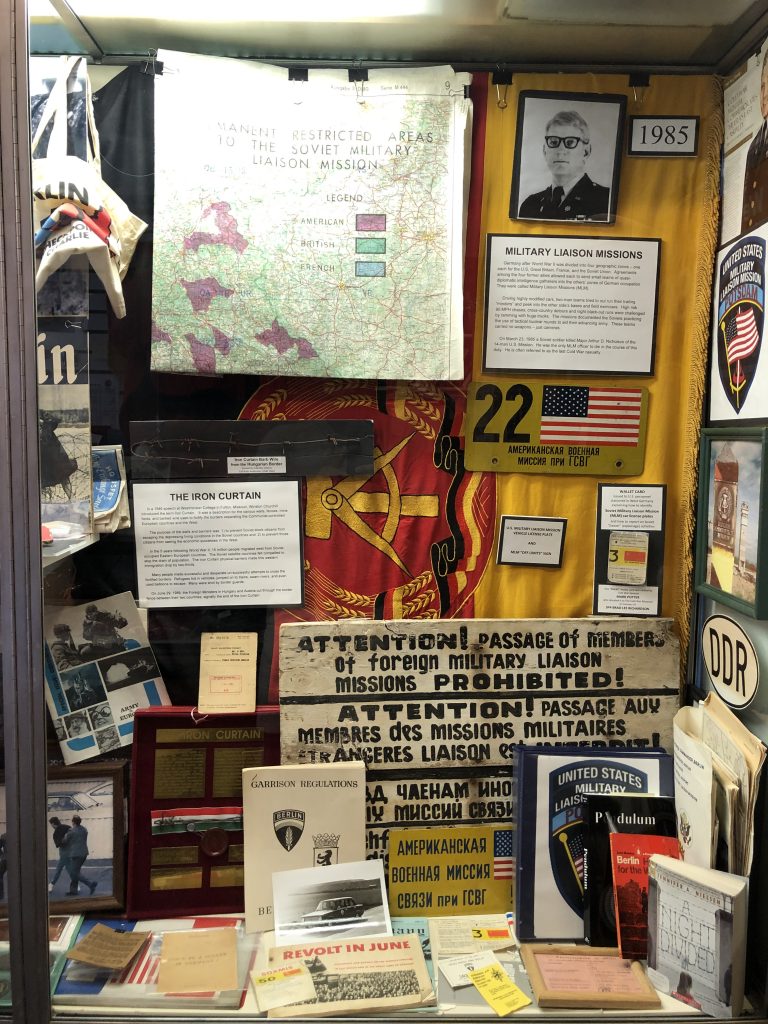

Spies in Uniform: The US Military Liaison Mission in East Germany

Beginning in 1947, a fascinating and little-known chapter of the Cold War opened in West Berlin with the establishment of military liaison missions between the United States, Britain, and France on one side, and the Soviet Union and East Germany on the other. What began simply as a means to jointly oversee German military disarmament during the post-war period soon turned into a perilous game of cat-and-mouse, as uniformed intelligence personnel from both sides pushed the envelope of international relations to collect actionable intelligence on each other, sometimes at the cost of their lives. With the ever-present specter of another World War hanging over the entire region, the Military Liaison Mission was a high-pressure assignment that attracted some of the most capable service members America could produce.

The service members assigned to the US Military Liaison Mission (USMLM) did not use many of the classic tools of espionage. There were no dead drops, no disguises, no confidential sources or hi-tech gadgetry. Instead, these courageous and cunning officers and NCOs worked openly, in uniform, known by all sides, to collect information on their adversaries. Their tools were binoculars, cameras, and notepads. Their methods varied from outrunning the East German Stasi in a high-speed chase, to offering a bored and lonely Soviet sentry a Marlboro cigarette and some conversation. Their primary mission was to collect actionable intelligence on Warsaw Pact equipment, tactics, operational tempo, and troop movements. They surveilled convoys and training exercises extensively, always on the lookout for a new type of issued equipment, vehicle configuration, or technological modification to the Soviet order of battle.

The Huebner-Mailinn Agreement of 1947 allowed for an equal number of liaison personnel from each country to operate in the others’ respective zones. The USMLM and Soviets agreed to allow fourteen total liaison team members at any one time. The USMLM had substantially more assigned personnel than this, around sixty normally. But only fourteen were ever permitted inside of East Germany at any given time, since that was the only place the Soviets could monitor their numbers.

Liaison team members drove heavily modified vehicles intended to give them advantages in all situations. A wide variety of US- and European-made vehicles were used over the course of the 40-year mission. Ford Fairlane and Galaxie police interceptors, Ford Broncos, Jeep Wagoneers, and later Mercedes Gelandwagens were all operated by USMLM. The US Army Quartermaster shop at the famed Berlin Brigade modified these vehicles for their unique missions.

According to Paul Nikulla, a Missionary from 1959-1962, the springs were replaced with heavier duty station wagon/ambulance springs. Koni shock absorbers replaced the stock item. Quarter inch thick steel plates were welded in place under the front suspension, engine and transmission as well as under the gas tank. German-type tow hooks were welded on the front and rear bumpers. Halogen headlights replaced the stock sealed beams. Additional halogen driving lights were added into the grill. The electrical switches were modified to permit the horn, head lights, parking and signal lights, and tail/stop lights to be turned off individually or all except the headlights with the flip of one switch. Original tires were replaced with Michelin all-terrain radial tires all ‘round. The whole vehicle, all but the glass was then painted a flat olive drab. A draw curtain was installed in the rear window. We also used the Jeep Wagoneer and the Ford Bronco modified in a similar manner. The all-wheel drive capability of these two SUV-type vehicles gave us additional cross-country mobility.

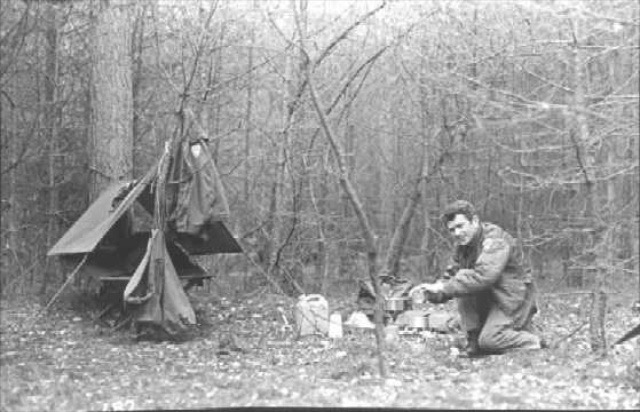

Team members operated in pairs and typically went out on a multi-day mission in East Germany, known as a “tour”. More than 600 tours might be completed in a single year. The team consisted of an officer who was fluent in Russian, and a driver/NCO who was fluent in German. Even on short-duration tours, the team packed in camping gear, extra food, water, and clothing along with their intelligence gathering tools. Getting stuck in bad terrain could leave the team stranded for days at a time, so they were prepared to be out much longer than anticipated. Heavy winches allowed them to get their vehicles unstuck on their own. Camouflage netting disguised them once they settled into an observation post.

Scavenger Hunt

In order to accomplish their assigned missions, team members had to be brazen and defiant in the face of their adversaries. While some areas of East Germany and East Berlin were thoroughly off limits in accordance with international agreements, the game was afoot everywhere else. Constantly chased and harried by the Soviets and East Germans, the Missionaries (as they called themselves) had to get creative in order to lose their pursuers and get access to the Soviet convoys and training cantonments that were their primary targets. Mission vehicles were equipped with a 44-gallon extended-range fuel tank because it was known that any time the vehicles stopped at a service station in East Germany, the attendant would phone in to the Stasi who would quickly home in on the location.

Retired USMC Major General Michael Ennis served with USMLM in the early 1980s, by which point the teams were issued night vision goggles and had equipped their Mercedes G-Wagens with infrared headlights. They could effectively disappear in the woods after dark, and Ennis reported that he had driven right past groups of Soviet troops who never even looked up. They would hear an engine nearby but expressed no curiosity since there was nothing to see. The teams also developed a ‘motorcycle configuration’ technique, shutting off all the lights on the right half of the vehicle so that only one headlight and taillight could be seen, effectively reducing their signature and disguising their vehicle to reduce suspicion from sentries.

Aside from taking photos and videos, Missionaries were expert scavengers. The Soviets often lost or carelessly left behind valuable tidbits of equipment or information. They frequently combed over bivouac and training sites from which the Soviet Army had recently departed. Their British counterparts, known as BRIXMIS, scored two enormous intelligence coups by combing over Soviet firing ranges. They discovered a damaged sabot round from a T-80’s main gun. The gun crew had been unable to load or fire it properly and discarded it over the side to be forgotten. This was the first round of this type that NATO had gotten its hands on and informed them of the Soviet’s anti-armor capabilities.

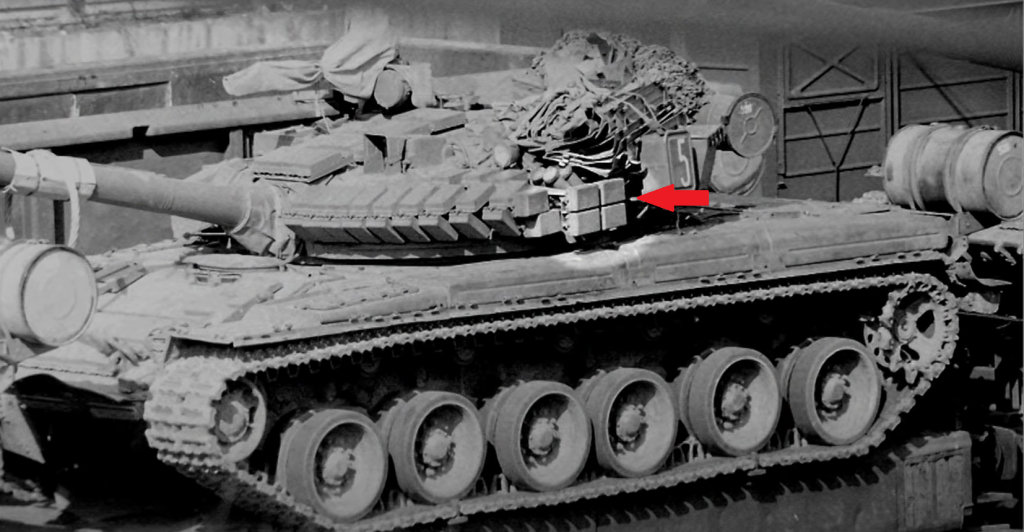

On another occasion, British intelligence officer Dave Butler discovered a half-buried Explosive Reactive Armor (ERA) box. The ERA was top Soviet technology of the time, and of tremendous interest to western intelligence agencies. The ERA was bolted on to the outside of Soviet tanks to detonate an incoming anti-armor round before it penetrated the primary armor. Its discovery represented an absolute coup for NATO and aided in the redesign of anti-armor tank rounds.

Missionaries found continual success with these scavenger strategies because the Soviet soldiers themselves almost never reported items as lost. There were immense consequences in place for anyone who reported the loss of a sensitive item, but inventory oversight was poor enough throughout the Soviet system that there was little chance an item would be discovered missing by higher headquarters on their own. So, the Soviet soldiers were thereby deterred from reporting lost equipment or ammunition Their loss was a Missionary’s gain.

One of the least glamorous aspects of their assignments came about due to supply shortages within the Soviet Army. Toilet paper was never issued to Soviet soldiers, forcing them to use whatever was at hand. According to Mike Ennis, who served with USMLM from 1986-1989, Missionaries would use gloves and sticks to look at used toilet paper found in the woods. Sometimes they struck gold as a careless Russian soldier would use a page torn from a code book or classified manual to do his business. No job was too dirty for the Missionaries.

Hard work and diligence paid off time and time again for the MLM. On one occasion, a Soviet airfield was being constructed in East Germany, and the runway had already been completed but was not yet under active guard. A Missionary team approached in the dead of night with a sledgehammer and broke up some of the runway concrete for analysis. It was determined then that the concrete was of a type that would be resistant to area-denial cluster-bombs used by NATO forces against Warsaw Pact facilities.

Separately, BRIXMIS members discovered a recently vacated Soviet site with a fire still burning in the center, with some paper documents visible through the flames. In a selfless and risky act, one team member literally dove into the flames to extinguish them immediately with his body. It turned out that the partially burned documents were Soviet cryptological documents. Even in their damaged state they provided valuable insight into Soviet communications.

High Risk – High Reward

The rewards were high for the Military Liaison Missions, but the risks were higher. None of the Missionaries from any of the services were ever armed at any point during the 40+ year mission. This led to high degrees of harassment and varying levels of aggression from Soviet and East German governments. A common tactic (on all sides) was to blockade a Mission vehicle to prevent them from leaving while a determination was made as to the legality of their activities. This was known among the Americans as getting ‘clobbered’. In most cases it was as much a rite-of-passage for Missionaries as anything else. Missionaries would be delayed and hassled by Soviet or East German soldiers, and then asked to sign a declaration that they were committing an illegal act. They would refuse to sign the form (as expected) and then be let go, losing nothing more than valuable time. This was what normally occurred, but there were many far more serious, and even deadly, encounters over the years. Between 1975 and 1987 there were at least twenty serious incidents between Warsaw Pact forces and the Missionaries. Numerous MLM vehicles were hit by gunfire and one driver’s boot was grazed by a 7.62mm round.

In at least one documented incident, the Soviets drugged an MLM officer at a December 1979 party between liaison group members, causing him to crash his official vehicle shortly after leaving the party to return to the MLM headquarters in Potsdam. The MLM hierarchy did not believe the officer, Major Bill Burhans, when he swore that he had not drunk irresponsibly at the party. Just after navigating the serpentine obstacles on the famed Glienicke Bridge near Potsdam, Burhans suddenly lost control of the vehicle, smashing into a bus. Burhans and his passenger, Lieutenant Colonel James Tonge were both returned to the United States in disgrace, their careers ruined. It was not until 40 years later that they would be redeemed when their full Stasi files were uncovered. Both men had been the targets of active Stasi operations for at least a year before the night of their fateful crash and had indeed been slipped drugs by someone during the Christmas party.

Over the years the Soviets developed a technique for deniable sabotage of the NATO liaison missions. When an identified Mission vehicle was passing a Soviet convoy, one of the large ZIL trucks would simply turn and smash into the small sedan or SUV, disabling it and injuring or even killing the occupants. The Soviets would immediately claim that there had been a tragic ‘traffic accident’ due to careless MLM drivers. Many US, British, and French vehicles were severely damaged or totaled in this manner. In 1984, French Liaison officer Major Philippe Mariotti was killed by a large East German truck. Stasi documents uncovered after the dissolution of East Germany by historian Mathias Heisig prove that Mariotti’s death was a targeted murder. The Stasi carefully tracked Mariotti’s movements and placed heavy trucks in waiting around the French liaison’s barracks. When the time was right, the trap was sprung. The Stasi launched into an aggressive disinformation campaign immediately following the crash, claiming Mariotti had been driving drunk and demanding compensation for the damage done to their vehicle.

Last Casualty of the Cold War

One of the greatest intelligence coups of the entire 40-year mission may also have ultimately been one of the costliest. In the early morning hours of January 1st, 1984, Major Arthur D. “Nick” Nicholson and his team scouted and successfully entered a Soviet tank shed containing the new-to-service T-64B Main Battle Tank variant. They likely took advantage of nearby Soviet personnel relaxing their security posture to celebrate the New Year. The team had unfettered access for 24 hours, an almost unbelievable triumph. Photos taken from inside the tank confirmed that it was capable of firing missiles and was equipped with a laser range finder. These photos were widely distributed among the NATO intelligence community and appeared the following year in the USMLM official history guide.

Nicholson was widely considered one of the most productive and capable of all Missionaries. This incident undoubtedly put him on the Soviet GRU’s radar.

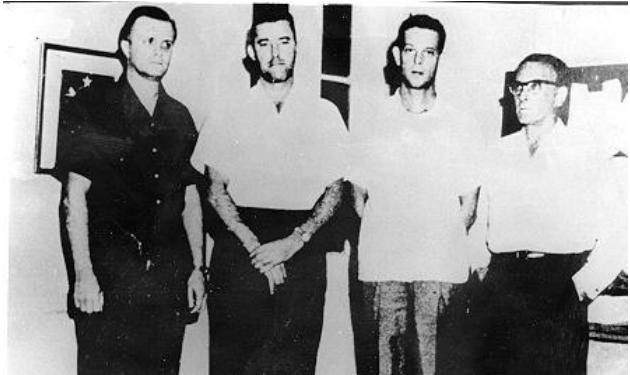

Although it did not come to light until many years later, it appears that Nicholson may have been betrayed and named to the Soviets and East Germans by James Hall, a US Army Warrant Officer who had begun aiding them in 1983. When finally caught and sentenced in 1989, Hall confessed to having provided the details of Nicholson’s intelligence coup to his handlers. What did they do with that information? We don’t know.

What we do know is that fifteen months later, on March 24th, 1985, Major Nicholson and his driver SSG Jessie Schatz followed a Soviet T-80 MBT convoy returning from training exercises. At the Soviet encampment they realized that there were no visible sentries posted. Nicholson exited their Mercedes G-Wagen and attempted to repeat history by moving to an apparently uninhabited tank shed to look inside.

At that moment a Soviet sentry moved out of the tree line and raised his rifle. His first round missed Major Nicholson as he turned and raced for the safety of the G-Wagen. The next round struck him in the chest, and he fell, mortally wounded. SSG Schatz attempted to exit the vehicle with a first aid kit to render aid, but the sentry forced him back into the vehicle as more soldiers swarmed in from all sides. Major Nicholson slowly bled to death as the Soviets debated what to do.

Nicholson’s death created an international crisis as both sides recognized what a major escalation it represented. The Soviets and East Germans went to work immediately sowing disinformation, as they always did. They claimed that Nicholson had been the aggressor, that he was trespassing in a forbidden area, and that they had acted in self-defense. US diplomats called for a Congressional investigation and sanctions against the Soviets. Ultimately the incident cooled down, and no one was held responsible for Nicholson’s death, whether it was murder or manslaughter. Nicholson was buried with full honors in Arlington National Cemetery. The Soviet Union officially apologized for his death in 1988, and in 2005 a memorial was erected at the site of his death near Ludwigslust, Germany. Nicholson would be the last official American casualty of the Cold War.

Germany Reunified

The NATO Military Liaison Missions persevered after Nicholson’s death for another five years, delivering up-to-the minute intelligence on Warsaw Pact forces readiness. As the Cold War wound down, the Soviet Union’s hold over Eastern Europe weakened. In November 1989 the Berlin Wall was finally opened and freedom rang through the formerly separated districts of Berlin. Over the coming months, the Missionaries turned their focus to observing the orderly withdrawal of Soviet forces from East Germany through Poland. Finally, on October 3rd, 1990, the two Germanys were offically reunified. That same day, the Military Liaison Mission was disbanded. The Missionaries went on to face new, emerging threats through different postings worldwide. Almost to a man, however, they unanimously report that their tours with the Military Liaison Mission were the best, most important, most dangerous, and most exciting times of their careers, and lives. Their accomplishments were decisive, and their sacrifices unforgettable.